It is a sign of how much nanny state activity there has been in Europe since 2019 that the United Kingdom has slipped from fourth place to eleventh in the table without liberalising anything. This can be partly explained by the government freezing beer and spirits duty since 2018 and freezing wine duty in 2020. Adjusted for income, its alcohol taxes are now only the ninth highest of the 30 countries in the index.

It also helps that the UK takes a common sense approach to e-cigarettes. There is no vape tax and there has been no gold-plating of the EU’s e-cigarette regulations. It remains to be seen whether the government uses Brexit as an opportunity for further liberalisation, but it remains highly paternalistic on food, soft drinks and tobacco.

Its smoking ban, introduced in 2007 (2006 in Scotland), allows fewer exemptions than that of almost any other country and was extended to cars carrying passengers under the age of 18 in 2015 (2016 in Scotland). In 2008, Britain became the first EU country to mandate graphic warnings on cigarettes. In 2011, cigarette vending machines were banned. A full retail display ban followed in 2015. In May 2016, the UK and France became the first European countries to ban branding on tobacco products (‘plain packaging’). The UK has the second highest rate of tobacco duty, although it falls to seventh once adjusted for income, and it has the highest rate of tax on heated tobacco at £234.65 per kilogram (€272). Overall, it has the worst score for tobacco in the index.

Vaping is banned on train platforms, in stations and on public transport, but is otherwise left to the owner’s discretion. A proposal by the Welsh government to ban vaping in ‘public’ places fell apart in 2017, but the idea may rear its head again now that its chief proponent, Mark Drakeford, is the First Minister for Wales. No such law has been seriously proposed in England, Scotland or Northern Ireland.

Scotland introduced minimum pricing for alcohol at 50p per unit in May 2018, with Wales following suit in March 2020. Off trade alcohol discount deals such as buy-one-get-one-free are also banned in Scotland. A UK-wide tax on sugary drinks came into effect in May 2018 at a rate of 24p for drinks with more than 8 grams of sugar per 100ml and 18p for those with between 5 and 8 grams per 100ml.

In recent years, most of the government’s nanny state activity has focused on its citizens’ diets. Food deemed to be high in fat, sugar or salt (HFSS) cannot be advertised during programmes that are mostly watched by the under-16s. This ban was extended to digital media in December 2016 and will be extended to all TV programmes shown before 9pm if the Conservative government’s obesity strategy is implemented in full. Ostensibly aimed at children, the strategy includes a ban on HFSS food discounts, a ban on displaying HFSS food at the entrance and checkout of shops, mandatory calorie counts in the out-of-home sector, and a ban on the sale of energy drinks (except coffee) to people aged under 18. The Scottish government has published an almost identical plan.

Britain’s score in the Nanny State Index does not reflect the full extent of the government’s meddling in the food supply. Under a putatively voluntary agreement with the food industry, Public Health England led a reformulation scheme aimed at reducing the amount of sugar in food by 20 per cent by 2020 and reduce the number of calories in food by 20 per cent by 2024. So far, the scheme – which has failed to have any impact on the nation’s sugar consumption – remains technically voluntary and so does not get any points in the index.

About

The Nanny State Index (NSI) is a league table of the worst places in Europe to eat, drink, smoke and vape. The initiative was launched in March 2016 and was a media hit right across Europe. It is masterminded and led by IEA’s Christopher Snowdon with partners from all over Europe.

Enquiries: info@epicenternetwork.eu

Download Publication

Previous version: 2019

Categories

About the Editor

Christopher Snowdon is the head of Lifestyle Economics at the Institute of Economic Affairs. His research focuses on lifestyle freedoms, prohibition and policy-based evidence. He is a regular contributor to the Spectator, Telegraph and Spiked and often appears on TV and radio discussing social and economic issues.

Snowdon’s work encompasses a diverse range of topics including ‘sin taxes’, state funding of charities, happiness economics, ‘public health’ regulation, gambling and the black market. Recent publications include ‘Drinking, Fast and Slow’, ‘The Proof of the Pudding: Denmark’s Fat Tax Fiasco’, ‘A Safer Bet’, and ‘You Had One Job’. He is also the author of ‘Killjoys’ (2017), ‘Selfishness, Greed and Capitalism’ (2015), ‘The Art of Suppression’ (2011), ‘The Spirit Level Delusion’ (2010), ‘Velvet Glove, Iron Fist’ (2009).

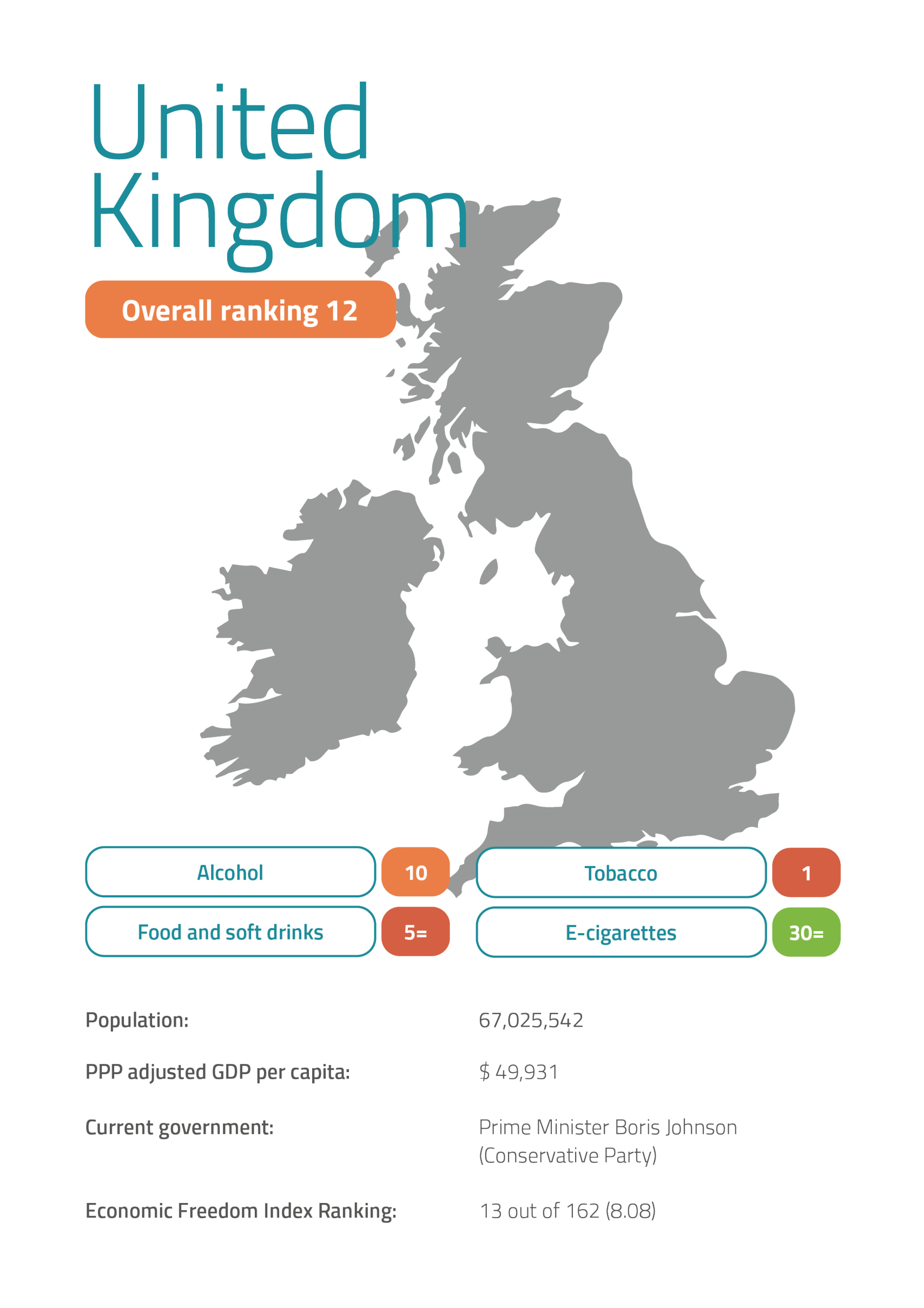

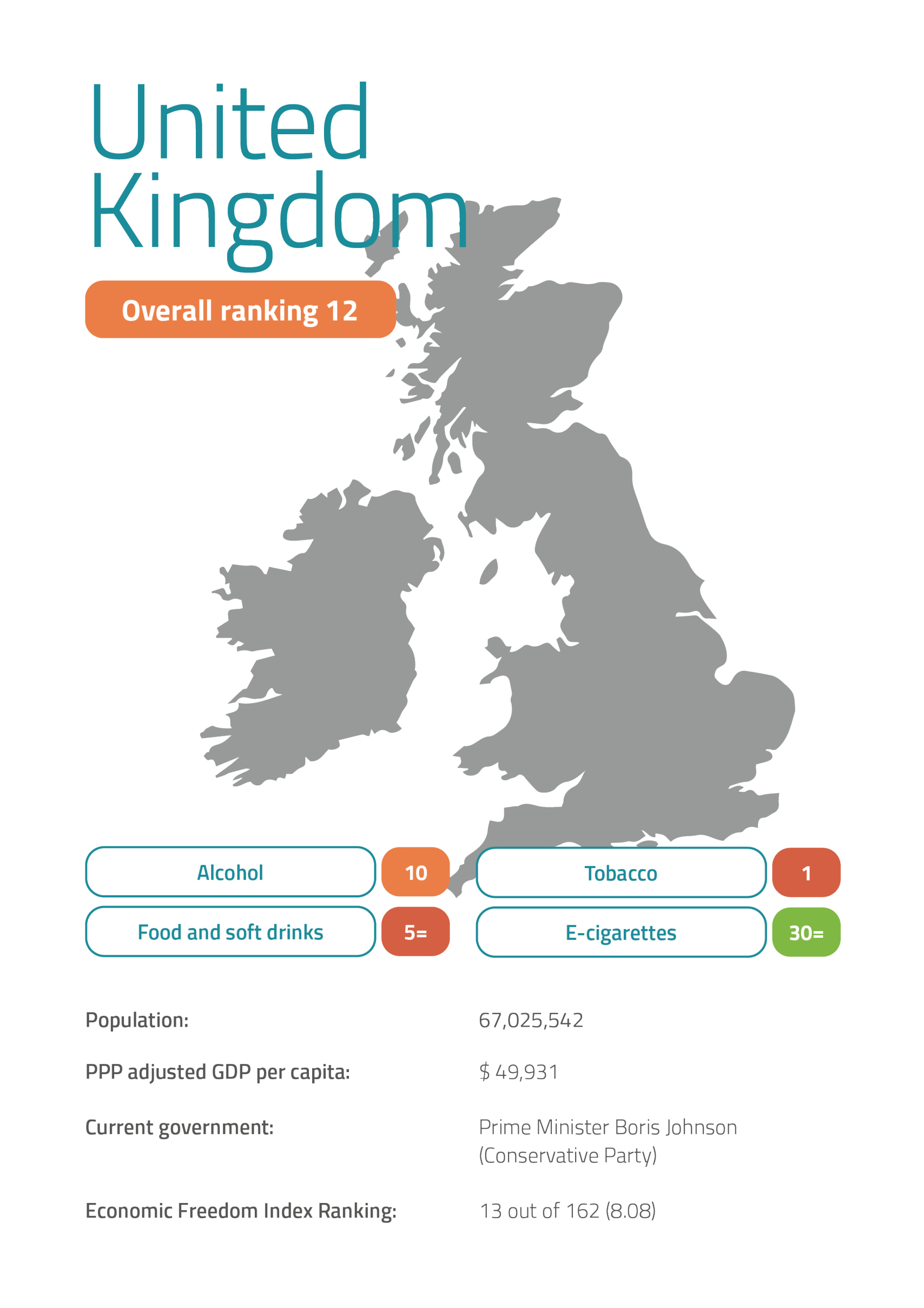

United Kingdom 2021

It is a sign of how much nanny state activity there has been in Europe since 2019 that the United Kingdom has slipped from fourth place to eleventh in the table without liberalising anything. This can be partly explained by the government freezing beer and spirits duty since 2018 and freezing wine duty in 2020. Adjusted for income, its alcohol taxes are now only the ninth highest of the 30 countries in the index.

It also helps that the UK takes a common sense approach to e-cigarettes. There is no vape tax and there has been no gold-plating of the EU’s e-cigarette regulations. It remains to be seen whether the government uses Brexit as an opportunity for further liberalisation, but it remains highly paternalistic on food, soft drinks and tobacco.

Its smoking ban, introduced in 2007 (2006 in Scotland), allows fewer exemptions than that of almost any other country and was extended to cars carrying passengers under the age of 18 in 2015 (2016 in Scotland). In 2008, Britain became the first EU country to mandate graphic warnings on cigarettes. In 2011, cigarette vending machines were banned. A full retail display ban followed in 2015. In May 2016, the UK and France became the first European countries to ban branding on tobacco products (‘plain packaging’). The UK has the second highest rate of tobacco duty, although it falls to seventh once adjusted for income, and it has the highest rate of tax on heated tobacco at £234.65 per kilogram (€272). Overall, it has the worst score for tobacco in the index.

Vaping is banned on train platforms, in stations and on public transport, but is otherwise left to the owner’s discretion. A proposal by the Welsh government to ban vaping in ‘public’ places fell apart in 2017, but the idea may rear its head again now that its chief proponent, Mark Drakeford, is the First Minister for Wales. No such law has been seriously proposed in England, Scotland or Northern Ireland.

Scotland introduced minimum pricing for alcohol at 50p per unit in May 2018, with Wales following suit in March 2020. Off trade alcohol discount deals such as buy-one-get-one-free are also banned in Scotland. A UK-wide tax on sugary drinks came into effect in May 2018 at a rate of 24p for drinks with more than 8 grams of sugar per 100ml and 18p for those with between 5 and 8 grams per 100ml.

In recent years, most of the government’s nanny state activity has focused on its citizens’ diets. Food deemed to be high in fat, sugar or salt (HFSS) cannot be advertised during programmes that are mostly watched by the under-16s. This ban was extended to digital media in December 2016 and will be extended to all TV programmes shown before 9pm if the Conservative government’s obesity strategy is implemented in full. Ostensibly aimed at children, the strategy includes a ban on HFSS food discounts, a ban on displaying HFSS food at the entrance and checkout of shops, mandatory calorie counts in the out-of-home sector, and a ban on the sale of energy drinks (except coffee) to people aged under 18. The Scottish government has published an almost identical plan.

Britain’s score in the Nanny State Index does not reflect the full extent of the government’s meddling in the food supply. Under a putatively voluntary agreement with the food industry, Public Health England led a reformulation scheme aimed at reducing the amount of sugar in food by 20 per cent by 2020 and reduce the number of calories in food by 20 per cent by 2024. So far, the scheme – which has failed to have any impact on the nation’s sugar consumption – remains technically voluntary and so does not get any points in the index.

Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Bulgaria

Bulgaria Croatia

Croatia Cyprus

Cyprus Czech Republic

Czech Republic Denmark

Denmark Estonia

Estonia Finland

Finland France

France Germany

Germany Greece

Greece Hungary

Hungary Ireland

Ireland Italy

Italy Latvia

Latvia Lithuania

Lithuania Luxembourg

Luxembourg Malta

Malta Netherlands

Netherlands Norway

Norway Poland

Poland Portugal

Portugal Romania

Romania Slovakia

Slovakia Slovenia

Slovenia Spain

Spain Sweden

Sweden Turkey

Turkey United Kingdom

United Kingdom